by Victoria Griffin

I’ve been writing fiction for as long as I can remember.

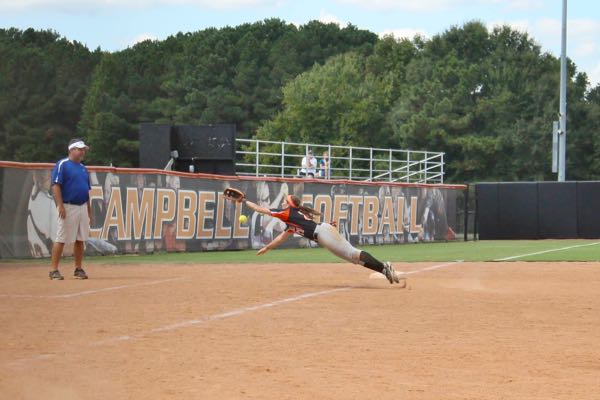

I published my first story my junior year of high school, and I knew going into college that I wanted two things: to write and to play softball.

On January 26 of this year I was one semester away from graduating with a BA in English and a week and a half away from the opening day of my senior softball season. That day, during practice, I took a hit to the head and sustained a concussion.

What was supposed to be a two-week injury turned into a four-month battle that completely derailed my plans. Now I’m using my experience and my passion for writing to help support others in similar situations and to spread awareness about the realities of concussions and brain injuries.

It’s Just a Concussion

I was stealing second during an intersquad scrimmage. The throw was up the line, and the tag came down hard on my helmet as I went to slide.

My helmet struck the ground, and the ball flew into right field. I got up, shook it off, finished practice, and went to night class. I knew immediately I was concussed. I had a headache, and my balance was off.

In class, I had trouble forming words, and I nearly fell down the stairs. But I had seen plenty of concussions. At a Division I school, they happened all the time. A concussion meant being stuck in your room for one to two weeks and having to go through the “return to play” program before being cleared for competition.

I was angry because I knew there was a good chance I would miss our opening weekend, which is why I didn’t want to mention my symptoms to my trainer. I hoped they would clear up in a couple days, as concussion symptoms often do, and I would get to play.

The day after the injury, I realized that was not going to happen. I went to class and tried to participate. I couldn’t seem to form words, and the light and sounds were like pins in my brain. My friends—whose faces were beginning to blur—urged me to tell my trainer.

At that point, my symptoms were more severe than any concussion I had ever seen, and they were about to get a lot worse.

Over the next four months, I was unable to read, write, or understand words being spoken to me. I was too weak to walk across my room, and the faintest light or sound caused unbearable pain. My short-term memory was nonexistent, and my personality and emotions disappeared.

In the realest possible way, I ceased to exist.

My Brain Attacks Me—Flooding

My Brain Attacks Me—Flooding

Sensory overload attacks, which I came to call flooding, were spurred on by the minutest stimuli—the sound of footsteps or even trying to think when my brain refused. When these attacks happened, I would be curled in a ball for hours. My muscles would involuntarily contract, and I would be unable to move or speak. I would forget how to breathe.

Basically, my brain would shut down completely, and my body would try to defend itself. I would wind up in a dark corner or in the doorway on a forty-degree night because my body was flaming hot. If a loved one found me and asked what was wrong, I couldn’t tell them, and the sound of voices only frightened me.

After three weeks, my team doctor sent me to a neurologist, who proceeded to saturate my system with drugs and insist that I “push through” these attacks.

The night after seeing the specialist was ER visit number one, caused by the medications that were supposed to help me.

Medical Treatments Make My Concussion Symptoms Worse

After a week and a half of his “treatment” I returned home to Tennessee to see a different doctor, who promptly removed me from all the medication and prescribed rest and patience.

I felt things might be turning around. The next day, I had ER visit number two. The next day I had my appendix removed.

At this point, I had attended two weeks of class, missed five, and had eight remaining. I had been able to complete only the minutest amount of schoolwork during my illness and was still unable to read or go out in public, including to my classes.

When I was finally well enough to return to school, I was in pretty poor shape. I couldn’t drive. Going to class was a terrifying experience. I never knew when my body would shut down. I never knew when my legs would give out and leave me stuck halfway between campus and my apartment, unable to walk.

My parents and professors kept telling me, “You can take a medical withdrawal and finish later. You don’t have to put yourself through this.”

I had already missed half a semester’s work. I couldn’t read. I could barely understand anything happening during class and couldn’t remember any of it. I could barely take care of myself, and there were many times I got stuck halfway up the stairs. Or worse, made it up and spent an hour unable to breathe. But I was going to get my degree.

Luckily, I have the best friends anybody could ask for. They slept on my floor when I was afraid I would stop breathing during the night, dragged me up the stairs, and carried me out of buildings when I couldn’t move. They gave me a chance to fight. I had already lost my senior season of softball, months of my life, my health, my fitness, my identity. I was going to get that piece of paper.

Recovery from My Concussion Was Long and Hard

And I did.

But it came at a price. Recovery was long and hard, and even though I have now been symptom-free for almost four months, I am still dealing with the effects—physical, psychological, and emotional.

Literature is one of the strongest tools I have for battling these effects. Writing helps me to reclaim my identity and to make sense out of the most senseless experience I have had.

Writing Is My Way of Making My Experience Real

So much about the concussion is unexplainable.

Any time I try to convey what I felt, it seems like I’m trying to explain the sound of the ocean to someone born deaf. The experience was so far from any reference point, I can never make another understand what it was like.

Writing is my way of making it real, of making the experience tangible. Anyone can read a story and slip into the character’s shoes. Maybe that way others can understand, at least a little, what it felt like.

Writing Creates Community

Writing serves another important purpose in my life: community.

I connect with writers on a deeper level, and over the last few years I have found great comfort in both online and local writing communities.

After my concussion, I have found similar comfort in communities of TBI (traumatic brain injury) survivors. Because the experience is so surreal and difficult to explain, connecting with a group of people who truly understand it helps to alleviate the stifling loneliness that comes along with the injury.

Losing your identity makes it difficult to connect with even people you love and to understand and express what you are feeling. Hearing others’ experiences actually helped me recognize emotional issues in my own life.

Writing Has the Power to Heal

Because of this incredible power of writing and community to heal, I couldn’t understand why there were no creative publications dedicated to concussions and brain injuries.

What could we accomplish with a publication specifically devoted to the topic?

We could provide survivors with an outlet to express experiences and sensations that are nearly impossible to describe outright. We could connect TBI survivors with others who have battled similar injuries. We could educate those who have not experienced brain injuries and concussions on a level more relatable and meaningful than simple facts and statistics.

We could grow together in compassion and understanding.

That is why I decided to create Flooded.

Flooded: Your Chance to Share Your Story

As a college athlete, most of my concussion “education” revolved around facts and statistics.

Obviously, since my first reaction was to hide my injury from my trainer, those numbers did not sink in. As a writer, I believe that the best way to reach people is emotionally, through stories.

So why not take the same approach to concussion awareness?

The plan is to create an anthology of fiction and creative nonfiction devoted solely to brain injuries.

The limitations are few—there is no requirement to have sustained a brain injury in order to submit work.

My line of thinking is that if someone who has not experienced a concussion or brain injury researches the injuries in order to write a thoughtful and accurate piece, we have already reached one person.

We will market the completed anthology to survivors of TBI, the literary community, the athletic community, and the general community.

We Need Your Help to Create This Anthology

Concussions don’t just happen during football games. They can be sustained during car accidents and falls. Absolutely anyone is at risk for sustaining a brain injury.

And, speaking from experience, waiting until you’re dealing with TBI to learn something about it is not the way to go.

To fund the project, I’m launching a Kickstarter October 11.

The campaign will run thirty days, and funds raised will go, first and foremost, toward contributor payments.

The money will also go to editing and proofreading, cover art and design, interior design and layout, Submittable fees, promotion, and backer rewards, which will include signed copies of the anthology, a “behind the scenes” eBook, discounts on books and editing services, a custom journal, and more.

After a successful Kickstarter campaign, a three-month submission window will open, during which submissions of fiction and creative nonfiction from five hundred to ten thousand words will be read blind.

Pieces will be selected, and the process of creating the physical anthology will begin.

I Want to Make it Easier for Other Victims

With this anthology, I feel that I have an opportunity to truly make alter the course of others’ lives.

I can’t help but wonder how different my experience would have been if I had read something like Flooded—or if my family and friends had.

The loved ones taking care of me, crouched beside me during attacks, would have given anything to understand what was happening in my body and mind. And I couldn’t tell them.

Perhaps, this anthology will give future victims and caregivers the perspective they need to make it through a life-changing injury and emerge stronger.

* * *

Victoria Griffin is a fiction writer and East Tennessean.

Victoria Griffin is a fiction writer and East Tennessean.

She is fond of books and peanut butter. She reads, writes, and edits, sometimes for money, sometimes for fun, and sometimes because the voices in her head tell her to. Her short stories have appeared in Atlantis, A Journey of Words, and Death & Pestilence.

Her home is in East Tennessee (think mountains and Dolly Parton). In the last four years, she’s attended universities in Indiana and North Carolina, but the Smoky Mountains are where her heart is.

Victoria has played softball her whole life, including DI college ball. She’s a die-hard Yankees fan and may or may not have cried when Jeter retired.

For more information on her and the Flooded project, please see her website, or connect with her on Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, and LinkedIn.

Flooded: A Creative Anthology of Brain Injuries: This anthology does not yet exist, but it should.

Flooded: A Creative Anthology of Brain Injuries: This anthology does not yet exist, but it should.

Will you help make it a reality by donating to our Kickstarter campaign?

Our goal is that Flooded will:

1. spread awareness about the realities of brain injuries through creative work.

2. provide a forum for those who have experienced brain injuries to express their own realities.

3. showcase brilliant writing.

It’s going to take many voices to urge Flooded into existence. I hope you’ll be one of them. Click here to read more, or to donate to the cause. After the Kickstarter period is over, see Victoria’s website above for more information.

I would love to be a part of this. I will keep in touch about both donating and submitting. Great cause. Writing does bring us together.

Thanks, Troy!! So appreciated. :O)

Thank you so much, Troy! I appreciate the support. 🙂